A research team from the University of the West Indies (UWI) has determined that antibody testing kits can be used to detect past SARS COV 2 infections in persons who had been symptomatic for at least 10 days.

SARS COV 2 is the virus that causes the coronavirus (COVID-19).

Providing details at a recent JIS Think Tank, Research Assistant in the Department of Microbiology at UWI, Tiffany Butterfield, who was part of the research team, said that the members assessed antibody assays to see if they would be able to detect past infections in the Jamaican population.

Antibody assays are tests that are used to detect antibodies in the blood. Miss Butterfield, who was the winner of the Most Impactful Presentation at the 2020 National Health Research Conference, noted that the study involved collaboration with the University Hospital of the West Indies (UHWI).

She explained that early in January 2020, the research team was able to isolate the SARS COV 2 virus, which enabled them to develop all the techniques and tools to be able to diagnose and detect COVID-19.

“That was a big point in the study, in terms of isolating the virus and creating all the steps that we use for detection,” she said, noting that by April 2020 the use of antibody assays had been authorised.

She said that all assays were being completed in high-resource countries like the United States and the United Kingdom (UK), among different types of populations – hospitalised, non-hospitalised, symptomatic and asymptomatic.

“We were, therefore, not sure if the outcome would be the same in our population. With that background, we decided that it was imperative for us to assess the commercially available antibody detection test kits to see if they would be similar to what is reported elsewhere, within our population,” the Research Assistant explained.

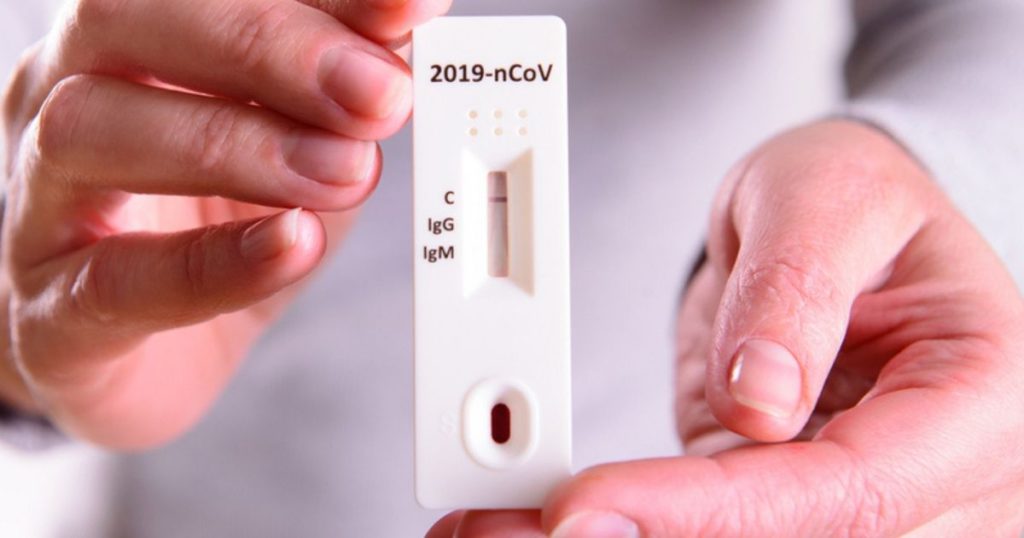

She said that one of the main features of the antibody detection kits is the detection of the immune response to the virus, and not the virus itself, which she explained, is what the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test does.

“One of the key things about that immune response is that your body develops the antibodies against coronavirus. Your body remembers the coronavirus. It has this immune memory that it can use to fight the virus whenever it resurfaces or you see/encounter the virus again,” she pointed out.

Butterfield said that an antibody test has the ability to detect current as well as past infection, “so when you get a positive antibody test it doesn’t mean that you actually have an infection going on right now. It could be that you had a past infection”.

The Research team started collecting samples in the summer of 2020 following approval from the UWI Ethics Committee.

“Our tests were accurately identifying our negatives. There were no false positives. We had a specificity of around 96 to 100 per cent for all the different platforms that we assessed,” Miss Butterfield pointed out.

She said the team found that the length of time the person had symptoms would affect the results of the test.

“So, if a person had symptoms for greater than 10 days, we were more likely to detect the antibodies, but if they had symptoms for less than 10 days, it’s a little harder for us to detect antibodies in that the sensitivity was a little lower – around 70 per cent,” she noted.

The Research Assistant said that samples were also taken from asymptomatic patients and those with mild symptoms.

“A lot of the assays that were done were on mainly symptomatic patients, so we wanted to look to see if it is able to also pick up those persons who never showed any signs of illness,” she pointed out.

“We then looked at our samples based on who had moderate, severe or critical illness and those who had asymptomatic and mild illness. We did see that there was an association of being more symptomatic and being hospitalised in terms of detecting your antibodies, than to being asymptomatic”,

she pointed out.

Butterfield said that another important finding was that severity seems to be associated with viral load, meaning how much of the virus is in the system.

She said the research team found that for those who had a higher viral load, they were more likely to detect antibodies for those infections.

This, she said, would suggest that the higher viral load was increasing the body’s immune response “giving a more robust immune response that remains after so that we are able to detect with our antibody assays”.